My mothers side of the family has had a somewhat checkered past. As a child we would visit this extended family once per year during the annual family reunion. Always at a safe distance. The gaggle of aunts, or I should more properly say grand-aunts, and the older female cousins that I thought were aunts, were primarily smokers and drinkers with gruff voices of the Marge Simpson variety but with a touch of class, or, the appearance of it. One was even married to a Lt. Col., a WWII veteran and war hero – a great pride to the family. There was also the great-grand-uncle Jack who was a close friend and manager of the icons Rita Hayworth and Orson Welles, among others. Whenever he made an appearance the family gathered around him like ants attracted to a sweet thing. I can’t blame them, I loved his stories of Hollywood’s golden era. He was particularly keen with me, being interested in theater, and with my father who made a hobby of script writing. If I had to pick a favorite, it would have been uncle Jack. The picnic reunions were an annual visit to a tableau of entertaining caricatures.

Dysfunction was a word that was never uttered but wholeheartedly understood. Behind what I saw as entertainment there were some darker stories. There was also the woman who had married a cousin, then had an affair with a drug dealer, who was murdered by her husband (my cousin) and subsequently sent to prison, during which time she remarried his brother and had sons with both. There was the branch that arrived on motorcycles and wore leather surrounded by whispers of the Hell’s Angels. There was the gay uncle – but the shame was not in his orientation – it was in their treatment to it. Something that I would take note of when I came of age and began to discover my own feelings toward others.

It seemed that there wasn’t a single branch that wasn’t entirely untouched, which led me to wonder… why? Was it a peculiarity of genetics? Maybe, very possibly. The question was left untouched for several years while I concentrated almost entirely on my father’s side of the family, the side which originally piqued my interest in this research that we are all now so fond of. But the time did come for me to look a bit deeper. My theory was that there was something further back that acted as the catalyst. And there was.

I didn’t know much in the beginning. I knew the name Paul Leighter or Leichter with some vague rumors that he was not present in the family. No one spoke of him. His wife Johnnie-Etta Bird Hastings, affectionately known as “Birdie”, my 2nd great-grandmother, was also rarely spoken of but always in good terms. She was remembered as having been an early female proprietor of a newspaper near San Francisco at the turn of the century who later dedicated her life to helping others by becoming a nurse. Orphaned in Fort Worth, Texas in the 1880’s, she and her half brother were brought to California and raised by a childless aunt. Although her early years were sad, she could not have been the cause. She was beloved. But Paul, what about Paul?

As he was born in 1871, I found him in only one census record with his childhood family. In 1880 he was living in a fine house on Clay Street in San Francisco where his father worked as a head clerk for importers, confirmed by the city directories. The nine year old Paul is listed as the son of Carl Leichter, age 35, with wife Julia, 22 and children Elsie age 3, and Edgar age 1. I immediately noticed the first clue of something that was a bit off. Carl and Julia were so different in age. But more telling, if Paul was 9, Julia would have only been 13 when he was born. Possible, but unlikely when considering that the next child was born six years later. It seemed that Paul was raised as a step-son and that his mother was no longer in the house. The 1900 census showed that he had joined the Army and was living in Bani, Philippines during the Spanish-American war. He had left his very comfortable life behind in San Francisco. It was shortly after this that he had married Birdie. Together they had four children including uncle Jack who later recounted to me that when, as a very young man who had lied about his age to join the army for the first great war, that he had been marching in line and in uniform down a street in Oakland when he spotted his estranged father. Jack tried to get his attention but he didn’t recognize his own son.

For several years that was as far as my research had taken me. Until I purchased a subscription to Newspapers.com and found a very distressing article published in the Oakland Tribune in 1927. Paul had run into some severe money trouble. He was a contractor in the middle of a project that was only half completed and he had spent the money that he was supposed to use to finish the work. He began living in the unfinished attic and the pressure was on. He made his way through most of the banks in the bay area looking for a loan. He tried one last one in Berkeley, and was again turned down. A friend had driven him and on their return to Oakland, while stopped at an intersection, Paul took a handgun which sat between the seats and shot himself in the chest. A suicide note was found in his jacket and the newspaper proceeded to publish its contents with a story of his suicide and death. The next day they printed a retraction, that he had miraculously survived the wound which just missed all of his vital organs. He was taken to Letterman hospital at the Presidio in San Fransico where he died, two weeks later, of pneumonia.

Finally a cause.

But something still ate at me. Yes, the actions of this man throughout his life and the taking of his own life, and what that might have done to his family, were certainly a cause for the scar that swept through the rest of the generations. But was this the original cause? Even here, this man, it was all brought on by his own actions. He left for war. He left his wife and children. He spent all of his money. He alienated himself. But why would he do that? Was this really the catalyst, or was there something earlier?

Then I remembered, his mother. What happened to his mother? Maybe that was it. I searched those newspapers again, and the city directories, and the voter registration, and the old San Francisco cemetery transcripts written when all the city headstones were destroyed and the graves moved to Colma several decades later – and I found more. His mother was Paulina Waterman, daughter of Martin Joseph Waterman (Wasserman), a jewish business man in the city. Interesting as her husband was Protestant. They had been married in the winter of 1870. She was only 16 years old, Carl was 26. They had Paul in 1871 and then a second son, Otto, in 1873. Both Otto and Paulina died within a couple months of each other, leaving Carl as a widowed single father. I later found elderly cousins, descendants of Paul’s half-siblings, who told me that Carl had been a stern father who insisted that only German be spoken in the house. He was thought to have been cold and distant. The records of his life indicate that he worked the exact same job for almost 40 years. Never going up. Always stagnant.

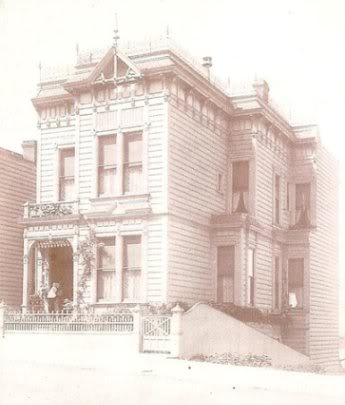

Perhaps he was content with this, or perhaps not. I found another newspaper article. This one in the San Francisco Chronicle and dated in 1899. One morning Carl said goodbye to his wife, as he had done every morning. He stepped out of his beautiful home on Vallejo Street in Pacific Heights, which he had built 10 years before, and which is still standing today greatly altered. He should have turned left, to head to his office downtown. Instead he turned right, and headed north toward the Presidio. At the small pier there, only a few yards from where his son would die 30 years later, he took off all of his clothes, folded them neatly and was never seen again. When his employer called to find out if he was alright, they discovered that he was missing. They checked his desk at work and a note was found. He had decided to commit suicide at least the night before, perhaps earlier. He wrote the note, left it in his desk, went home, had dinner, went through his routine, saw his wife and family, went to bed, woke up, had breakfast, and said goodbye – all the time knowing what he was going to do. Never giving anyone any hint to his intentions.

I mean, really, no wonder Paul was the way he was. As much as I vilified him before, I could suddenly understand him.

But that feeling came again. I understood Paul. But now I didn’t understand Carl. Yes, he had lost his wife at a young age. But many people have gone through that hardship. Why was he so stern? Why did he take his life? Because he led a sedentary life? Isn’t that true for almost everyone in the world?

Again, I had hit the end of my research and still with questions that I didn’t understand. Until a few years later when I found the church records where Carl was born. I finally understood.

Carl was the son of Friedrich Wilhelm Leichter and Antoinette Elisabethe Strohecker – Huguenot descendants of Neu-Isenburg, Germany (near Frankfurt). Friedrich and Antoinette had at least 13 children, many of whom died young. But nothing out of the ordinary for the time. Friedrich was born in the same place in 1815, listed as “Guillaume” on his birth record as the family was equally as French as they were German – common with Huguenot families. His parents were Andre Leichter and Susanne Catarine Koch.

I learned that Andre and Catarine had nine children, but ALL of them, with the only exception being Friedrich, died young. The first was Ernestine, born in 1813. Although I haven’t found her death record they would name another daughter Ernestine later. Then Friedrich in 1815. The next two siblings Philippine in 1817 and Jean Jacob in 1819 would live longer but we’ll get back to them. Then the real trouble began in 1821 with the birth of Marie. She died in 1823 at the age of 2. Friedrich was 8 when his little sister died. Then in 1824 the 2nd infant Ernestine died, Friedrich was 9. In 1826 the infant Anne died, Friedrich was 11. In 1830 the infant sister Wilhelmine died, Friedrich was 15. A final sister, Margaretha was born in 1834 and survived, but tragedy turned back to the older children now. Philippine died in April 1839, unmarried, at the age of 22. Friedrich married Antoinette in July 1839, they married because she had become pregnant – the daughter also died shortly after birth. Then their father Andre died that Dec 1839. Friedrich was only 24 and now only had two siblings left out of eight, both parents dead, and married with one child already buried. All before the age of 24! Then Friedrich’s daughters Elisabeth (1843) and Julianne (1846) died as infants. Then his brother Jean, in 1848 at the age of 29, also unmarried from what I can tell. Friedrich was 33 now. Then Friedrich lost more children in infancy: Peter (1850) and Ernestine (1851). Friedrich’s last surviving sibling, Margaretha, died in 1854 unmarried at the age of 20. Then Friedrich lost three more children in infancy: Maria Theresia (1855), Maria Magdalena (1857), and Antoinette (1859).

Friedrich witnessed the death of 18 immediate family members (parents, children and siblings) between 1814 and 1859 – by which point he was only 44 years old. It was at this same time that his remaining children began leaving for California. Johann in 1856, Carl (my ancestor) in 1859. A final daughter Maximilianne was born in 1862 and also eventually joined her brothers, whom she had never previously met as they moved before she was born. I think it was this constant tragedy in Friedrich’s life that made him bitter and caused his children to push away and fall into depression. A ripple affect that is still being felt today.

So I suppose the moral of all of …. this… is that – if we have tragedy in our lives we must do our best to deal with it and process it with as little repercussion as possible. If we don’t, it could have lasting affects on future generations.

Stay strong my friends!

Such an interesting family! I love reading these blogs. Please, keep them coming!

LikeLiked by 2 people

WOW, what a story! thanks for sharing

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is what I am finding, that it isn’t always pretty what we dig up. No matter, we must come to terms and accept, if we can, and better, gain understanding of the whats and whys of our predecessors. It truly does filter down. This is a great post. 🙂

LikeLike